Saving a bird. Save the birds.

A cedar waxwing had an encounter with our window. Its survival reminds us of the ongoing threat to America's bird population.

A few weeks ago I was in my wife’s studio when we noticed a group of birds flitting about on the barren branches of a large hibiscus outside about 15 feet away. Suddenly one smacked into the window and flew to a nearby boulder on the hill where it rested for a few seconds, then slumped and slid down the side of the rock and onto the ground.

I hurried outside to pick up the bird and hustled it back into the studio, cradling it in my palms. Its eyes were open but it looked stunned, or worse. It then occurred to me to see what kind of bird this was. It was a cedar waxwing, identifiable by its sharply drawn black mask that stretches from ear to ear across its eyes, its tawny breast, small tuft at the back of its head and patch of lemon yellow at the tip of its tail, there as if it had been dipped in a pot of paint. A cedar waxwing also has a red dot on each wing resembling sealing wax on an envelope, though I don’t remember seeing one.

It’s a beautiful bird, one that lives here year-round but doesn’t present itself often, especially in winter.

Katie, who instinctively knows what to do in situations like this, got the bird onto a small white towel and began blowing warm air onto its face. It wasn’t moving but did not seem distressed. We placed it into a small cardboard box, closed the cover to keep it safe and warm and texted Ben Nickley, who’s the director of the Berkshire Bird Observatory and knows as much about birds as anyone, and asked him where we could take it for help.

He told us there’s a trained rehabilitator named Marguerite Nicastro in Ancram, New York, about 30 miles to the west of us. We drove the bird to Ancram and dropped it off with her at her office, an insurance agency in the village.

She assured us she’d give it a full examination and told us to hope for the best.

The next morning she texted to say the bird was fine. It had regained its senses overnight, which she told us was not an unusual amount of time for a bird to remain in a stupor after the trauma of striking a window. Nothing was broken, thankfully.

We’d done the right thing by taking it indoors, keeping it warm and seeking help. If we had left the bird outside it would either have frozen to death, been eaten by predators or both. It was a helpful reminder of how to treat an injured bird.

Marguerite said it would be best if we released the bird in our yard. Cedar waxwings, she told us, tend to congregate in groups – they’re called an earful, google it – and this would give it the best chance of reuniting with its crew. We drove back to Ancram to pick it up. The bird was still in its box, quiet but very much alive.

When we got home we carried the box out to the boulder on the hill outside the studio and opened the top. After sitting still for maybe half a minute, the bird suddenly was gone. It flew off so fast that my effort to record the release on video failed.

I’ve realized since that we never asked whether it was a male or female.

We haven’t seen cedar waxwings back on the property since, though they’re around. We’ve been going on bird walks along the Housatonic River most Saturdays organized by the Berkshire Bird Observatory and last weekend the trees along one stretch of the bank were filled with multiple earfuls.

It was a cheerful note in the midst of the ongoing decline of our native bird populations.

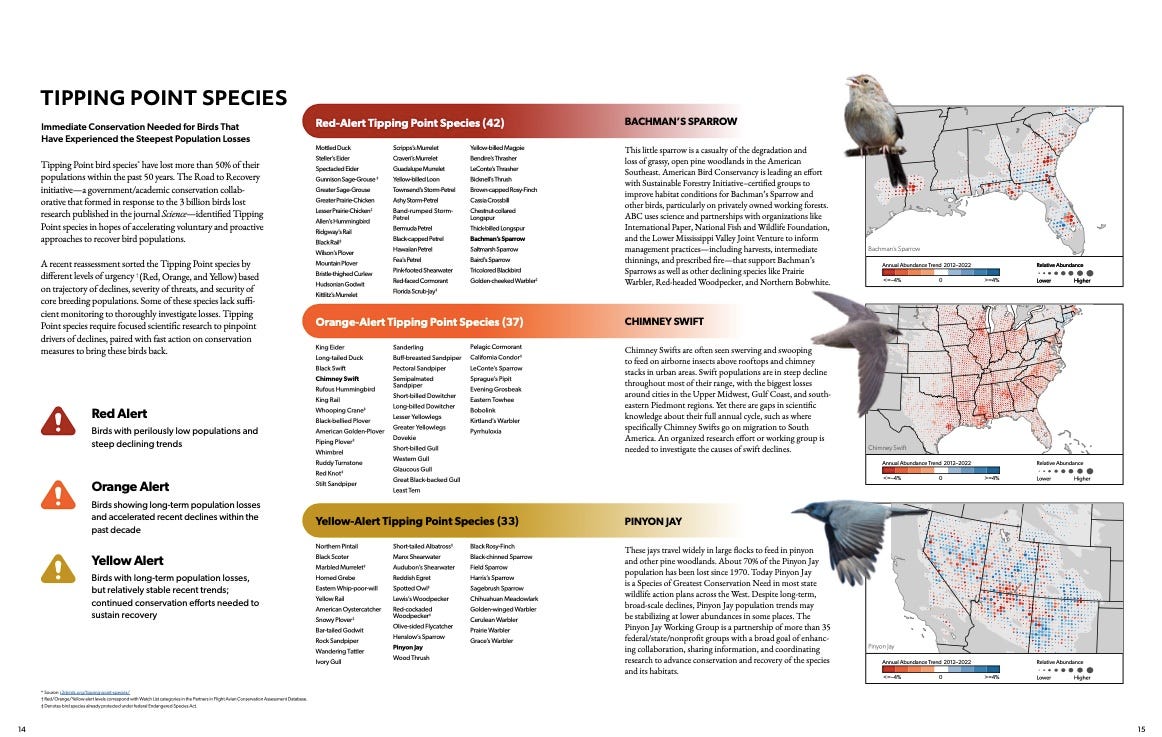

A new report was released this month just as the spring bird migration period approaches with sobering new data on birds in the United States. The report, by a consortium of governmental and nonprofit organizations called the North American Bird Conservation Initiative, follows a landmark study five years ago that revealed the United States had lost more than 3 billion birds over the previous 50 years, or 30 percent of the total bird population.. That decline continues. The new report says the state of more than a third of U.S. bird species are of high or moderate concern and “require urgent conservation attention.”

Of particular concern are birds found only in grasslands or arid landscapes, it says. Those populations are down more than 40 percent over the past 55 years. But almost every region and habitat in the United States is affected. The report notes sharp declines in forest birds in the Northwest as well as bird populations in the Northeast, along the East Coast, and the Southeast. A new alarming development is a steep decline in duck species, a seeming reversal of a group of birds that had been a more positive note in recent studies.

Overall, the state of our birds is not good, and the reasons are many.

“The rapid declines in birds signal the intensifying stressors that wildlife and people alike are experiencing around the world because of habitat loss, environmental degradation, and extreme weather events,” said Amanda Rodewald of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Center for Avian Population Studies.

The report lists 112 “tipping point” species, those whose numbers have declined more than 50 percent over the past half-century. Among the 42 species with perilously low populations are the Bachman’s Sparrow, Prairie Warbler, Red-headed Woodpecker and Northern Bobwhite. Other birds experiencing long-term population losses and accelerated decline include the Chimney Swift, Evening Grosbeak, Eastern Towhee and Bobolink.

The report stresses the importance of conservation efforts to preserve habitats.

Can saving one bird matter, especially in the face of such enormous odds seemingly at work against these beautiful creatures? I hope so. I hope our cedar waxwing is still flying in the fields and woods around here.

Judy Pasko runs a small rescue in northwestern Massachusetts called Cummington Wildlife. She does it on her own with a staff of one, her husband. She specializes in the rehabilitation of songbirds, game birds and wild rabbits.

She gave a Zoom presentation earlier this month sponsored by the New Marlborough Land Trust and I listened in because of our experience with the cedar waxwing. (Full disclosure: I’m also a member of the land trust board.)

She said it’s not always easy when you see a bird on the ground to know whether it needs assistance. This is especially true when it comes to newborns. In our case, it was easy because we saw the cedar waxwing hit the window.

She listed a number of signs that indicate a bird is in distress and needs help. One of the easiest to spot is if its eyes are closed. It’s a clear signal the bird is unwell. Another indicator is if it’s puffed out, its feathers fluffed. We might assume that’s the sign of a healthy well-fed bird, she said, but it more likely shows it’s under duress and is having trouble keeping warm.

Handle an injured bird at a minimum, she said. When you do, the only precaution nowadays is to wash your hands because of the danger of avian flu. The same advice holds true when you clean or add food to feeders.

A clear sign of head trauma, she said, is when a bird is having trouble standing or when it perches on your hand and does not fly away. This was the case when we picked up the cedar waxwing that hit our window. It had every chance to fly off, but instead sat immobile in the box. Until, that is, the day we brought it back home and it flew off into the woods, hopefully to reunite with its earful.

Here’s a selection of other recent posts:

Bending the zone in a vegetable garden

How to start seeds. Begin with good soil, water and light.

Starting seeds takes a little planning. Here’s how.

As the thaw begins, be grateful for the snow. Your plants are.

Some of my favorite seed catalogues, and what makes them special

How great (in these times) to read a story with a happy ending... thanks for posting