The outdoor temperature is supposed to climb into the 40s for several days this week for the first time in months. It’s been a bitterly cold winter, with only a handful of days above freezing since mid-December.

The ground has been covered with snow for much of it, which prompted my wife and I to finally make good on our promise to each other and buy a couple sets of snowshoes. We christened them when we awoke to a six- or seven-inch layer of fresh powder one morning and had a beautiful hike up the hill and woods at the rear of our property. We made our way along the old trail, clambering over logs from fallen trees and identifying the modest trail marks from rabbits and birds that had greeted the day and fresh snow ahead of us.

By evening, our region was being pelted by heavy snow and freezing rain driven by fierce winds that cut into the exposed skin of your face as the temperature plummeted. By the following morning every outdoor surface was entombed in an impenetrable layer of snow and ice that cemented the ground, driveway and paths and made venturing outdoors without metal cleats attached to your boots a death-defying experience. It remained that way for more than a week. But relief has finally come.

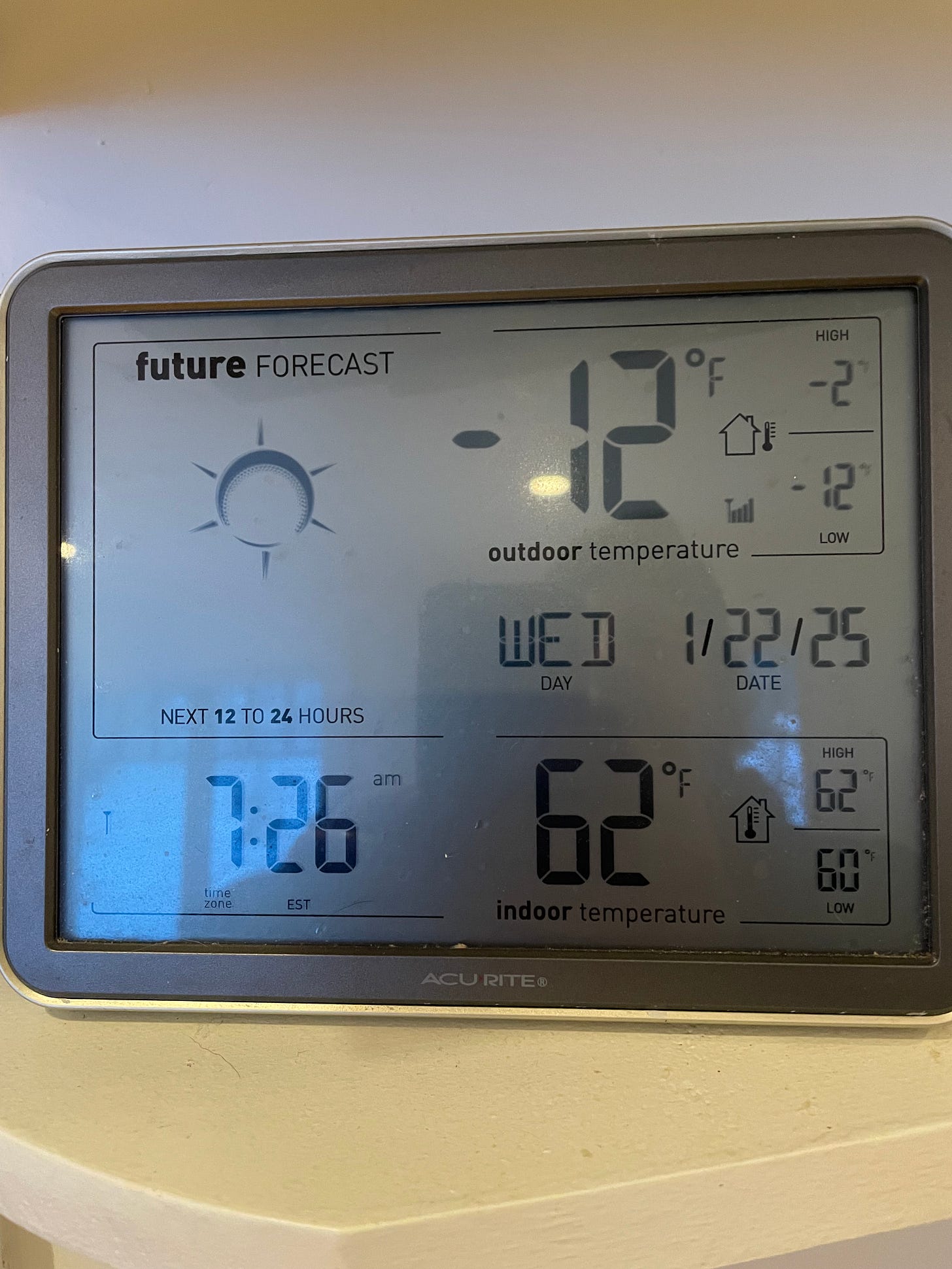

I don’t know when or how I became the designated weatherman in my household but it is now one of my roles in life. None of this was planned but for a variety of reasons we have two digital outdoor thermometers, one on the west side of the house inside the breezeway connected to an app that also measures rainfall totals and wind speeds from monitors out in the field, the other on the southern side outside the kitchen door that relays temperature and humidity levels to a display on the counter that also gives us an illustrated weather forecast for the next 24 hours based on the barometric pressure. I also have three weather apps on my phone.

I’ve actually been known to triangulate between them because they can be at odds with each other sometimes.

All of this is to say I can safely confirm that all systems are pointing toward daytime highs in the 40s here in western Massachusetts through most of the work week. The ice and snow are shrinking a bit and finally showing signs of melting, though the fields and woods surrounding our home are still blanketed in a beautiful carpet of white. They look all the more magnificent as the days lengthen in late winter and the afternoon sunlight casts long shadows across them in shades of amber and violet.

For those of us eager to get out into the garden, a stretch like we’ve had this winter can seem interminable. Which it has been, except it’s useful to remind ourselves that snow cover is a good thing for plants and the soil. As gardening author Lee Reich pointed out on his blog last week, “If we’re going to have cold temperatures, we might as well have snow.”

Snow insulates the soil, especially when it’s thick enough, creating pockets of trapped warm air “like a fluffy down jacket,” as an article published by the Brooklyn Botanic Garden put it. Snow cover provides shelter for rodents and other mammals and allows the dormant roots of trees, shrubs and perennials to shut down for the season in peace without subjecting them to the upheavals of cycling frosts and thaws. They’ll readily resume their growth as soon as the temperature begins to rise. I’m happy to include here our three-year-old asparagus patch, which has been entombed in a half-foot of snow and ice. It will be mature enough this spring for our first real harvest.

Snow also helps retain moisture in the soil. When it snows early in the season and the ground stays covered, the temperature of the soil below may not even freeze much. This allows earthworms and other soil microbes to continue doing their work. I’ll be interested to see how the soil in the perennial borders and vegetable garden responds to this year’s snow blanket.

One thing I did learn as I was poking around the Web is that all of this cold and ice will have absolutely no impact on the tick population, which seems unfair.

I was searching for examples of how snow cover affects soil and plant life and what I came across was telling. Study after study, article after article, focused on the impact of declining levels of snow in the Northeast as our climate warms.

It’s no secret that winters like this one have become the exception. It’s been several years since the Berkshires have experienced a winter this cold and with this much snow. I was talking to a landscaper the other day who grew up here and he said this was a typical winter – 20 years ago. It’s a pattern that’s true for much of the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic.

A 2020 article published by the Yale School of the Environment said research shows that more than a quarter of the Northeastern United States does not experience any significant snow during a typical winter nowadays. That will increase to 59 percent by the end of the century. Connecticut and Pennsylvania could be snow-free by then, a study by the University of New Hampshire’s Earth Systems Research Center said.

The vernal window – what we all fondly know as “mud season” – will begin earlier and last much longer, the UNH study said. More concretely, declining levels of snow melt will affect soil moisture and groundwater levels, affecting how nutrients from soils are discharged into rivers and fish migration and mating patterns.

What all this means for the backyard gardener remains to be seen, though it’s further evidence that the changing growing patterns we’ve been experiencing will continue in the years ahead. As with many things in the world these days, though, I’m narrowing my focus at least for a bit and taking pleasure in the beauty and benefits of an old-fashioned winter.

Next I’ll get to enjoy the Big Melt that will finally expose the garden soil.

Here’s a selection of other recent posts:

Begin with a good soil mix, water, light and go from there

What beautiful writing, and what peaceful landscapes. I look forward to reading more about your garden's Spring awakening